During the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, my grandma was almost exactly the same age as I am currently. I remember learning about this in school and being bemused at how the world had allowed itself to traverse the precipice of species-wide annihilation, but I can only imagine how terrifying it must have been for people like her to live through it. Robert McNamara makes the crucial point that we ultimately had a favourable roll of the dice in the 60s:

"I want to say, and this is very important: in the end we lucked out. It was luck that prevented nuclear war. We came that close to nuclear war at the end. Rational individuals: Kennedy was rational; Khrushchev was rational; Castro was rational."

In the 60 years that followed, the world has scarcely approached the threat level of that time. The prolonged period of relative tranquillity since the Cuban missile crisis has seemingly lured some into a false sense of security, however. This long uneventful period did not occur by accident — the near misses of the early 1960s traumatised decision-makers into taking the possibility of nuclear war incredibly seriously, and pursuing policies that by and large sought to de-escalate than inflame geopolitical tensions. The period of detente that followed involved the US and USSR compromising with each other, signing SALT 1 in 1969 which involved a bilateral agreement to freeze the number of strategic ballistic missile launchers at their current levels. Indeed, the closest we have come to nuclear conflict since then came from a non-conflict source in 1983, when a false alarm alerted Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov that the US had launched 5 ICBMs. Luckily for humanity, he had the good sense to realise that a true attack would involve far more missiles and so was able to convince his superiors not to escalate this any further.

This recent lack of nuclear crises has seemingly lulled some in the West into a false sense of security, evaporating the respectable levels of caution which were present previously when geopolitical tensions rose with a nuclear-armed country. Nothing has exemplified this more than the response to Russia’s awful invasion of Ukraine, with members of the commentariat, as well as politicians, suggesting that NATO should declare a no-fly zone (NFZ) over Ukraine. If you are unaware of what this means, you may well think it is something quite innocuous and simply involves establishing military borders in the air as we do on the ground. The phrase disguises the process that underpins it, which would involve NATO forces shooting down any Russian planes that dared to breach the declaration (which they almost certainly would). As such, establishing an NFZ would be tantamount to the start of world war 3. In fact, I don’t think this is strong enough since the plausible path of escalation quickly approaches all-out nuclear war.

To be clear, I don’t blame the Ukrainians for asking this of the west. They are undoubtedly in the midst of an existential crisis and it would be irresponsible of them to not exhaust all possible options to aid their cause. What is equally irresponsible is the failure of people in positions of power in the UK and US to not denounce it as a form of humanity-wide suicide, instead seriously entertaining it. There was this exchange between Daria Keleniuk, a Ukrainian advocate, and Boris Johnson:

Tobias Elwood who is, incredibly worryingly, chair of the British Defence Select Committee, argued that it would be "misleading, simplistic and indeed defeatist to suggest engaging in an NFZ over Ukraine would automatically lead to a war." So we should be comforted by the fact that it would merely raise the probability of nuclear annihilation significantly, not guarantee it. I can sleep easy now. Worryingly still, it seems that this idea has a decent level of support amongst the public, although I think this may largely be down to many not really knowing what the move would entail.

We can consider the effect of an NFZ through the lens of an expected utility framework. Of course, this is very stylised, but the central point is useful I think. Suppose some social planner is maximising the expected utility which they gain by keeping as many people alive as possible, and they are risk-averse. Their utility function is given by:

Where D is the total number of deaths and the γ parameter indexes how risk-averse the social planner is. Clearly, utility is decreasing in the number of deaths and is maximised at zero. Suppose that imposing an NFZ either saves a significant number of Ukrainian lives or leads to an escalation that results in a nuclear war between Russia and the west. A plausible estimate of how many people worldwide could die in this latter scenario yields a figure of 90 million. The estimate of nuclear war happening between the US and Russia in a ‘normal year’ is estimated at 0.25% by this thorough survey:

Let’s assume that imposing an NFZ would save 1 million lives (I think this is wildly optimistic) with some probability 1- π if it goes to plan, but there is also the possibility that it leads to nuclear war which leads to 90 million dead which happens with probability π. This figure comes from this piece of research here, but to be honest I think the true number could be much higher. What would the highest tolerable probability of nuclear war be in order to make an NFZ the highest utility option? Expected utility from an NFZ is given by:

Expected utility from not imposing an NFZ and instead maintaining the status quo is:

We can then solve for a π* such that the two are equal, meaning that π* will represent the highest possible risk of nuclear war we are willing to tolerate such that an NFZ is still our optimal action. First, if the social planner is risk-neutral with gamma = 0 then the only thing they care about is the expected number of deaths in each case. This means that if the expected number of deaths from an NFZ exceeds 1m then it will not be optimal, which is the case if π > (1/90) = 1.1%. I think you could easily make an argument that it is likely an NFZ would push π well above this level, and remember this is with some parameter values which are quite generous towards the policy.

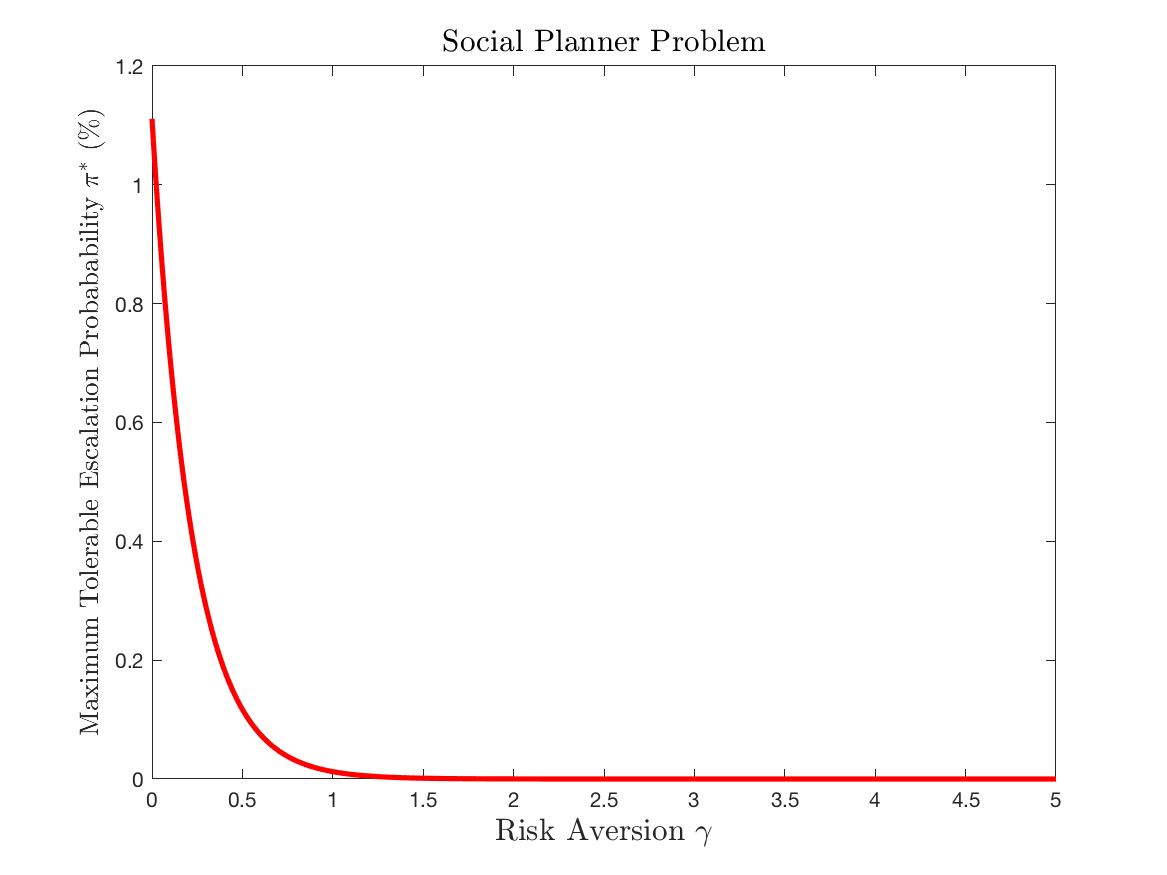

But what about if the social planner is risk-averse, as indeed we would expect them to be? The graph below plots the level of π* for a range of γ values. As risk aversion increases, the maximum nuclear probability we are willing to accept decreases precipitously and rapidly approaches zero.

The reason for this is that a risk-averse decision-maker adjusts the probability of the different scenarios for how disastrous they would be. These risk-adjusted probabilities place a much higher weight on the nuclear war state of the world since this represents an utter catastrophe for the planner. A risk-averse social planner can therefore be seen as a risk-neutral one who places much higher subjective probabilities on bad states relative to their true likelihood. With a γ of 1, probably a very reasonable value, the social planner is not willing to tolerate a nuclear probability of anything greater than 0.012%. Looking at the table above I think it is pretty clear that an NFZ would certainly lead to a much higher probability than this.

The most common counter-arguments to these usually involve the evocation of some game theory principles — the well-known concept of mutually assured destruction (MAD) is the most common of these. The idea behind this is that nuclear escalation by one side in the conflict would invariably lead to equally destructive retaliation by the other side, meaning that there is no way in which it could ever be rational for Russia to be the first to use nuclear weapons. With this principle in mind, the West could do whatever it wanted, short of firing nukes at Russia, without having to worry about nuclear escalation. I wish I could ever be as sure about a model as those who believe in MAD are, to the extent that they are essentially willing to bet millions of lives on it holding true.

To be clear, I think MAD has a lot of merits and clearly worked well as a deterrent during the Cold War. But, I think it worked more by encouraging both sides not to antagonise the other at all, rather than encouraging both sides to inflame situations up to the point of nuclear war. Also, MAD only works if everyone is rational. I think Putin likely is rational (by this I mean that he is maximising some objective function, obviously not that he is acting in a morally correct way), but I would not say I’m 100% sure of this. If there is even the slightest possibility he has gone crazy then MAD does not work at all. As such, it would be a terrible idea to test his rationality with an NFZ and find out.

The invention of nuclear weapons changed international relations irrevocably. Oppenheimer’s famous quote that he had “become death, destroyer of worlds” was no exaggeration. In some ways, their existence has arguably saved millions of lives, as the Cold War would almost certainly have been hot if not for the nuclear deterrent. However, just because we got through without their usage then does not mean that this is an inevitability in the future. Deterrence only works if it deters, meaning that the West should always keep the possibility of catastrophe in mind when making strategic decisions. Thankfully, it does seem as if those making these decisions are very wary of the situation, with cooler heads prevailing so far. Let’s hope for the sake of all of us that it stays that way.