Difficult Life Decision? Try Flipping a Coin

Have you ever found yourself agonising over a decision, whether it was an important or unimportant one, only for events to play out in such a way that you ended up regretting how much effort you put into the decision in the first place? For the more neurotic amongst us, myself included, this can become particularly frustrating in the case of minor decisions — what to wear today, what to have for lunch etc — as it certainly seems that our ultimate happiness level will not change much regardless of the decision we end up making. The standard framework in economics dictates that a decision is made through the lens of expected utility maximisation — in simple terms, I make the decision that I believe will yield the highest risk-adjusted benefits. While this approach may be a little less suited to minor decisions (I don't personally believe that people make a careful cost-benefit inspired analysis when deciding whether or not to have the 7th beer of the night), for bigger decisions in life, surely this careful analysis of risk and reward pays dividends? This certainly would have been my prior belief until recently when I came across this paper by Steven Levitt, the author of the well-known book Freakonomics.

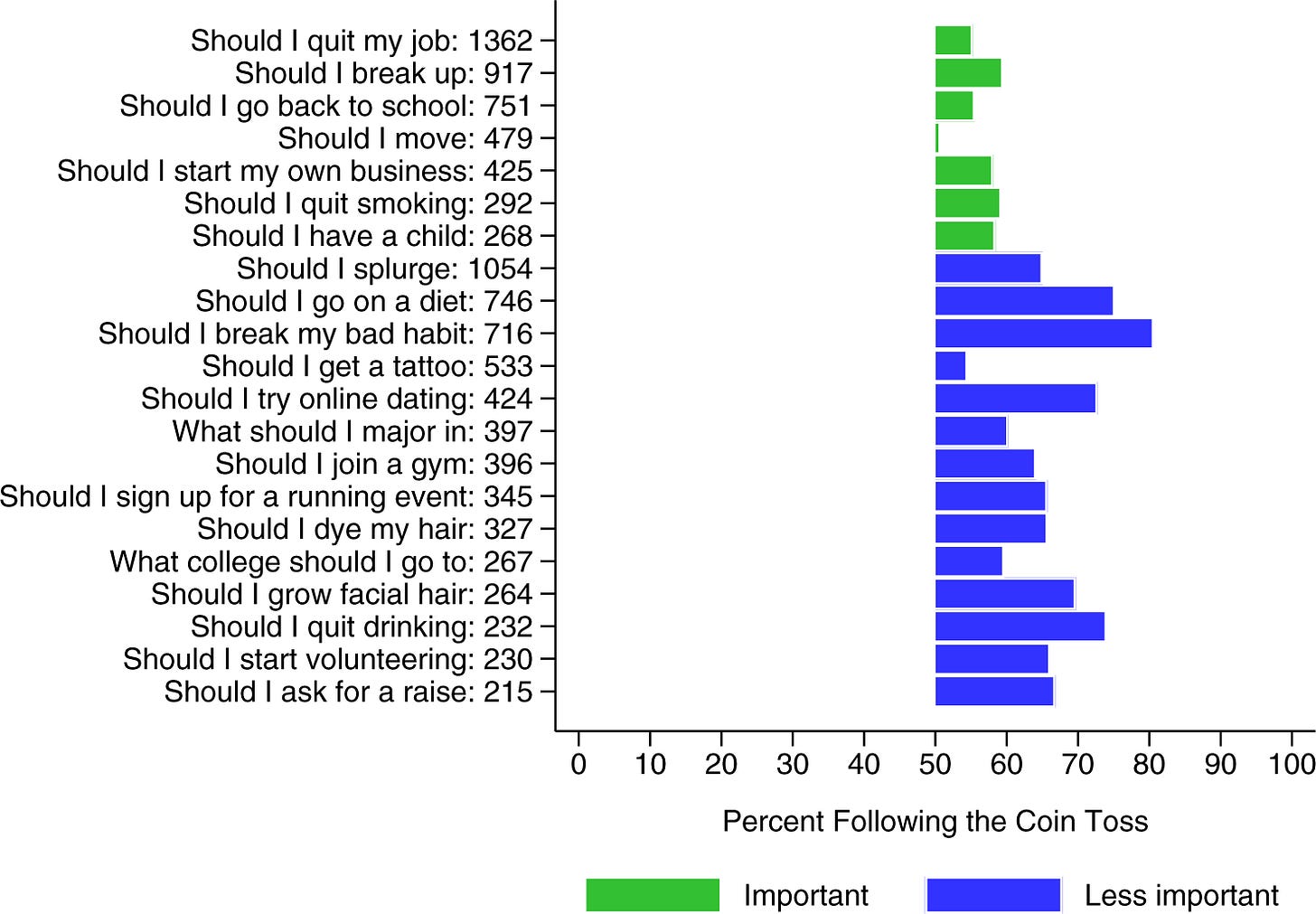

In this paper, Levitt conducted one of the most interesting behavioural experiments I have come across, where a website was created which encouraged people faced with a difficult life decision to allow the outcome of a coin toss to potentially influence their choice. If the coin came up heads, the participant would be encouraged to make the decision which involved a change (e.g. getting a new job) and if it came up tails they would be told to maintain the status quo (e.g. remaining in the current job). Of course, no one could be compelled to actually make the decision which the coin toss prescribed, but many of the 20,000 people who took part did abide by the outcome when told to make a change. Perhaps this is a notable finding in itself, as it suggests many people do find themselves at the margin of these important decisions.

The most interesting result, however, was that those who were assigned to make a change, and subsequently did so, reported increased levels of happiness six months afterwards. This is at odds with the standard expected utility framework - those indifferent between breaking or maintaining the status quo should obtain the same level of happiness on average regardless of what they end up choosing. The fact that this is not what was observed during this experiment suggests that there is a status quo bias, as individuals exhibit a tendency to underestimate the benefits from making a change and to overestimate those from keeping things as they currently are. I certainly find this relatable, as when faced with such a decision I often find myself viewing the change option as unnecessarily risky - the old adage of 'the devil you know is better than the one you don't' often springs to mind. After the fact, the majority of the times I have made a difficult decision to depart from the status quo, I have not regretted it. To be clear, this status quo bias is a different concept from risk aversion, which is a characteristic of preferences rather than a bias. A more risk-averse person would be more likely to rule out a risky option entirely, and so therefore would not find themselves on the decision margins at all. Further to this, a second interesting result from the study was that those who were randomly assigned to make a change were substantially more likely to report that they made the correct decision and that they would make the same decision again if given the chance.

The paper ultimately makes a compelling case that there is a general tendency amongst the population to exhibit a strong bias against making a change when it comes to important life decisions. While I do not think this a universal phenomenon by any means, as I think there is a subset of people who perhaps exhibit the opposite problem of having a 'grass is always greener' mentality, it is certainly a bias that I exhibit at times. Next time I am on the margins during an important decision, perhaps I will just flip a coin and see how it goes.

Try it, you might like it

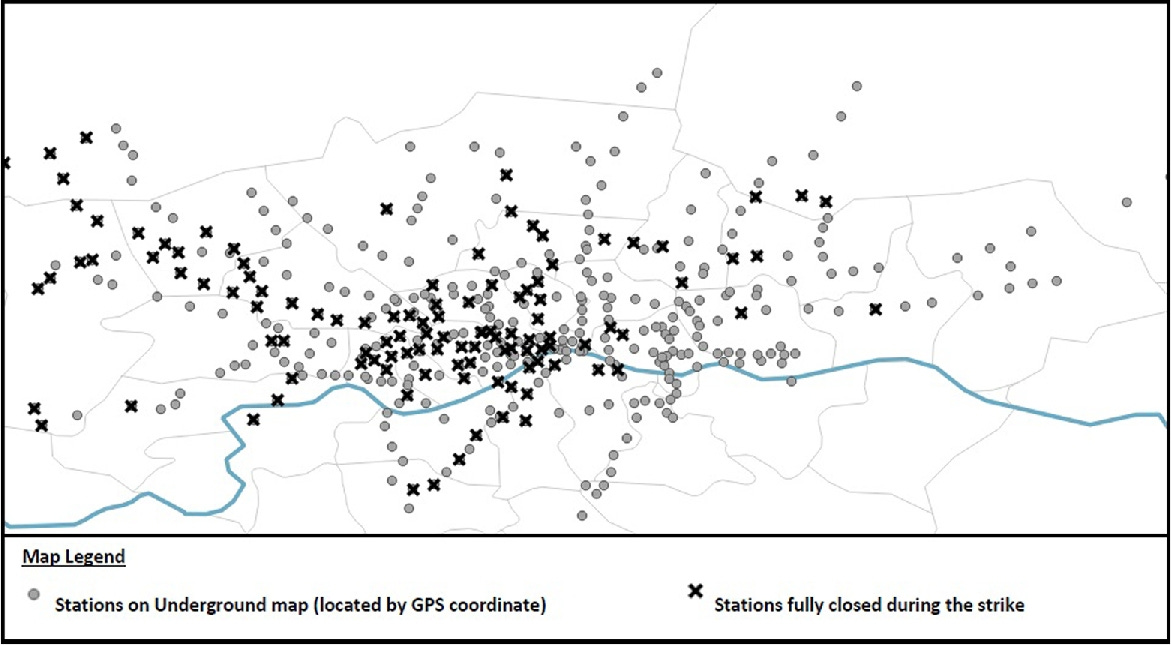

A second interesting paper related to similar issues of decision making suggests that the status quos which many of us fall into vis a vis many of the things we do on a daily basis are not optimal. The study looked at the impact of a two-day Tube strike in February 2014, where 171 out of 270 tube stations closed at least partially, forcing a large number of people to deviate from their usual commuting pattern by taking alternative routes to and from work. The fact that some of the network remained fully open meant that there was a natural control group of commuters whose journeys were not disrupted. Those of you who have some familiarity with the London transport network probably know that route planning is by no means a simple, linear exercise. For example, there are at least 13 reasonable ways of getting from King's Cross to Waterloo. This has since been made a lot easier through the growth of apps like Citymapper, but this was not prominent during the time of the Tube strike. The many possible alternative routes make it plausible that commuters do not optimise and choose the best one, rather getting stuck in a habitual pattern that they do not break voluntarily.

By looking at Oyster card data, the paper finds evidence that this was indeed the case. Many of those who were forced to experiment and select a different route to work on the strike days ended up adopting these new journeys going forward rather than going back to their habitual ones. Note that the strike only lasted two days, which is not plausibly long enough for these changes to be explained by the formation of new habits. In a funny sort of way, the Tube strike actually was beneficial to this group by making them deviate from their normal patterns and discover a more preferable route. Of course, there was nothing apart from habituality preventing them from willingly conducting this experimentation themselves.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a much wider and larger scale source of forced experimentation and the results of the paper suggest that this could be highly beneficial in terms of allowing people to discover areas of sub-optimality. The most obvious example of this has been the rise of remote working, a concept which previously many employers viewed with a high degree of scepticism as they were of the view that would lead to a reduction in worker productivity due to reduced monitoring ability. As a result of government policy, many employers have had no choice but to introduce home working for the better part of the last year. It is hard to imagine anything which would have led many of these firms to conduct such a trial voluntarily. It would also seem that many employers consequently believe that allowing for home working is strictly preferable to the previous paradigm of full-time office work, as large surveys of firms suggest that the overwhelming majority will keep some degree of remote working as a permanent practice even when full (new) normality resumes.

Similar to the status quo bias which was the focus of the first part, it would seem that there are potentially substantial benefits from experimenting more frequently, particular for those of us who are prone to forming rigid habits.