How Did Epidemiologists Get It So Wrong? Part 1 of 2

In November 2008, Her Majesty the Queen visited the London School of Economics to open a new building. During a briefing by LSE economists on the build-up to the turmoil on the international markets, the Queen asked: "Why did nobody notice it?". This was emblematic of a backlash against economists following the Financial Crisis, which was perhaps best epitomised by an Op-Ed in the New York Times from Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman entitled 'How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?'. Now while I think this backlash was not entirely justified, not least since economics is such a broad discipline that the majority working within it do not focus on macroeconomics (although I happen to), I am of the opinion that a portion of the criticism did ultimately impact the field for the better. For example, since the Financial Crisis, there has been a myriad of interesting and useful research on financial frictions, credit markets and inequality that probably would not have emerged if not for the discipline attracting this increased scrutiny. It is with this in mind then, when I say that epidemiology seems ripe for a similar transformation. Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, the predictions of many high-profile epidemiologists have been consistently well off the mark, and what has been more dispiriting is that the lessons from these mistakes do not seem to be learned. Broadly speaking, these errors can be categorised as follows:

1. Over-estimation of the impact that policy has on the dynamics of the pandemic.

2. Lack of emphasis on non-policy induced behavioural change as a mechanism of transmission reduction.

3. Exaggeration of confidence levels when making forecasts.

I will cover the first of these below and the last two in my next post.

1) Over-estimation of the impact that policy has on the dynamics of the pandemic.

Reading the fervent coverage of government decision making during the Covid-19 crisis, anyone could be forgiven for thinking that policymakers have a large degree of control over the pandemic. If cases get too high, then politicians can just put their foot on the brake pedal, bringing them back down to manageable levels via policy changes (lockdowns primarily). Back in September/October, some epidemiologists, SAGE included, and, in fact, the Labour party called for a circuit breaker two-week lockdown to stop the second wave in its tracks. Not doing so, according to some, spurred a devastating second wave that led to a more severe lockdown eventually. When the UK government did not put India on the travel red list, they were accused of letting in the Delta variant “through the back door” and allowing “leaky borders”. Many felt that this decision condemned the country to a painful third summer wave. Finally, when the government decided to continue with the relaxation of almost all Covid restrictions on July 19th, despite cases being high and continuing to rise, they were deplored as wilfully "letting it rip" through the population

I’ll offer an alternative theory applicable to these three cases: policy really does not matter. Or, to be less provocative, policy matters much less than we think it does. Take the circuit breaker case - Wales actually did opt for a circuit breaker two-week lockdown in contrast to the rest of the UK. They went into lockdown on October 23rd, unlike England which did not lockdown until November 5th. This provides a quasi-experiment, meaning we can use Wales as a treatment group of sorts and compare it to England which serves as the control group in order to try and assess the impact of this circuit breaker lockdown. In fact, we will use the three English regions which border Wales as the control areas, since these are likely to have case growth patterns that are more similar to Wales. The method we will be using is a difference-in-differences event study, where we essentially compare the change in the growth of new cases/deaths between Wales and the English regions before and after the circuit breaker was implemented. The key identifying assumption needed here is parallel trends – essentially that cases/deaths were growing at the same rate before the circuit breaker in the treatment and control groups, and would have continued to do so in absence of the policy intervention. Thankfully, we can test this first part.

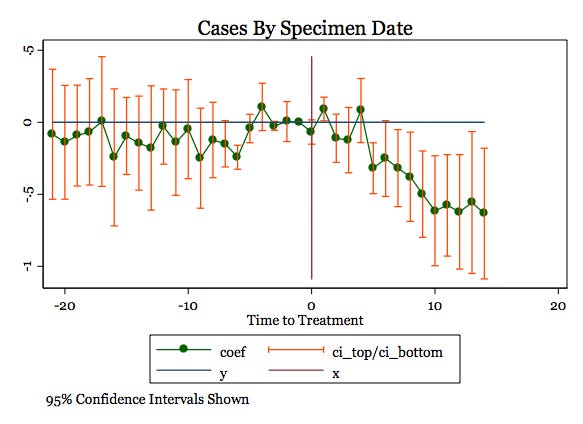

I estimate the event study first using data on daily new cases by specimen date in each of the areas from Public Health England. Cases are in logs since they are growing exponentially, meaning parallel trends can only hold in logs. Since it takes around 6 days from exposure to symptoms, and people don't tend to get tested before symptoms appear, I assume that the treatment date is 6 days after October 23rd. Results were robust to ranges from 3-10 days, however. I will truncate the post-treatment period to end on November 11th, since this is 6 days after England went into a national lockdown. I use the 3 weeks prior as the pre-treatment period, although this is not particularly consequential. The event study plot is below.

The left side of the graph shows that parallel pre-trends are plausibly satisfied, as the confidence interval for almost every point contains zero within it. The right side of the graph shows that after about 5 days, (log) cases started to be significantly lower in Wales than in England – the confidence interval contains only points below zero and so we can reject the null hypothesis that the circuit breaker had no effect on cases in Wales relative to the control areas. I tried a few placebo tests, where I picked a random day where there was no circuit breaker announced and tested whether there was the same effect present, and there was not. Therefore I feel reasonably confident in saying that the circuit breaker did lower measured cases in Wales, relative to the counterfactual, during the two weeks after it was implemented.

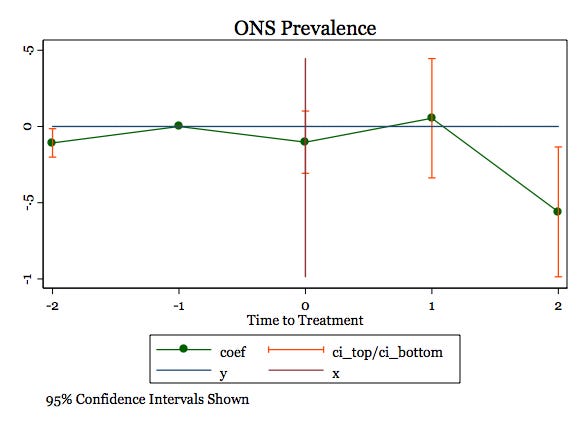

A possible problem with measured cases is that testing was highly non-random at this point in time, which could create a selection bias problem. To alleviate this, the ONS do a study where they randomly test people to gain an unbiased idea of Covid prevalence. I repeated the exercise using this data, which is measured over two week periods and so is at a much lower frequency. I use the two periods prior and the two periods after as the pre- and post-treatment periods respectively. The event study plot is depicted below, and the same result emerges as Covid incidence is estimated to be lower in Wales relative to the counterfactual in the post-treatment period. This only shows up two periods after the circuit breaker is implemented, however. This is likely due to the fact that people can test positive for a long time after getting infected, which is picked up by the ONS study and results in significant lags being present.

So we have looked at cases so far, but what about deaths which is what we primarily care about of course? Since research shows that on average the period between infection and death is 26 days, I use 32 days after the circuit breaker began as the treatment date. As the plot below shows, the results are much less clear. Even being extremely charitable, I really can't see a reduction in deaths here. When experimenting with the treatment date, this didn't really change either.

The lack of a reduction in deaths may seem hard to reconcile with the robust fall in cases, but I will offer two potential explanations. Firstly, perhaps the increase in reported cases was not truly representative of an increase in the prevalence of Covid and was instead due to selection bias. The eventual decline in the ONS measure makes me think that the fall in cases was genuine, though. The second explanation is that, as with every policy, a lockdown works on the margins. What I mean by this is that there are groups of people distinct in their responses. There is a group of people who, lockdown or no lockdown, would not have gone to the pub or gone shopping out of caution or for other reasons. Analogously, there is a group of people who will engage in social activities regardless of whether or not it is permitted. Neither of these two groups will have their behaviour substantially affected by the imposition of a lockdown. The group that will experience behavioural change consists of those who will engage in such activities when there is no lockdown but will not do so if there is a lockdown. As such, there is a subsequent change in cases in this set of individuals. The problem is that this group is likely to contain people who are at lower risk of dying from Covid, i.e. younger, healthier individuals and so the reduction in cases does not translate to a fall in deaths. To give a concrete example, the circuit breaker prevented people from going to pubs and I imagine that this disproportionately impacted younger people, who may have otherwise caught Covid but were extremely unlikely to die from it. Older people and people more at risk were more likely to exercise caution and abstain from going to the pub, regardless of any policy in place. Consequently, the circuit breaker did not impact the number of deaths that occurred, which surely was its ultimate goal.

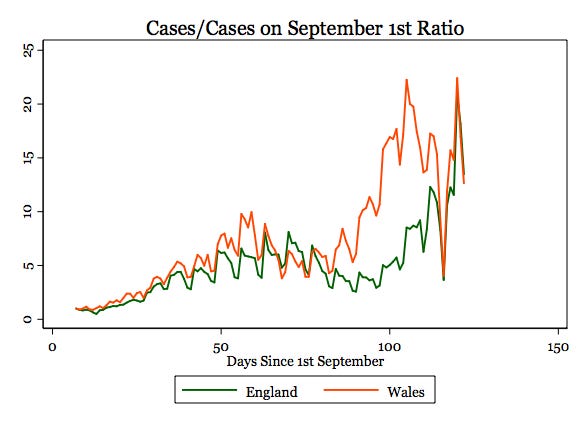

A second point made in favour of the circuit breaker was a 'stitch in time saves nine' type of argument – by locking down early, it was possible to gain back control of the dynamics of the pandemic and prevent a longer, more painful lockdown down the road. While this argument is harder to evaluate, since England also ended up going into lockdown in November, I also do not buy it. The data just does not seem to support this at all, as the figure below illustrates. It plots the number of new daily cases in England and Wales relative to the number of cases in each respective nation on September 1st, roughly the start of the second wave. The orange line of Wales is clearly well above the green line of England for a substantial period of time, meaning that cases had risen to higher levels relative to where they started in Wales. This is the exact opposite of what the above argument would have predicted. In fact, one could even make the argument by looking at the graph that the circuit breaker helped in the short run but actually worsened things in the long run. What I think is more plausible is that it had a limited impact on dynamics, certainly far less than its proponents suggested.

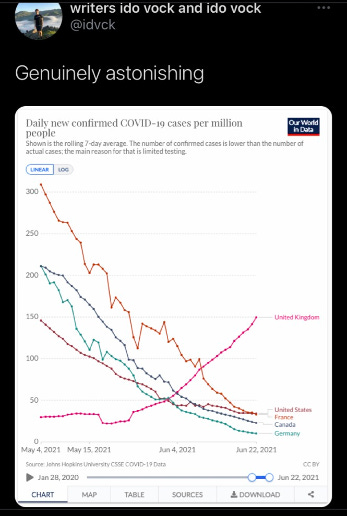

Turning to the issue of the Delta variant's seeding in the UK, as I mentioned previously there were many commentators who felt that this was enabled by the lack of expedient action on travellers coming in from India. In my opinion, it is clear that this did indeed cause the Delta variant to take root earlier in the UK than in other countries, but I do not think that banning travel from India early would have prevented the third wave and instead would have only delayed it. The below tweet was heavily shared:

But if we look at these countries now and use a log scale (which you should unless you are deliberately trying to mislead):

Well, what do you know, Delta also seeped into France, the US and Germany (to a lesser extent), causing a very similar pattern of case growth. Even Australia, who took the draconian measure of threatening anyone returning from India with a $50,000 fine and have consistently had some of the most punitive border policies of any nation, are now experiencing a Delta-induced wave. I really find it hard to accept that it is possible to keep a variant out through border closures as a result. It may have been possible to delay the wave through such measures, which would have allowed us to vaccinate more people, but given that we had already offered a vaccine to all those vulnerable or aged over 50 at this point, I think the impact of this would have been second order. Once again, it is easy to point to policy failings here, but ultimately this is ascribing far too much power to the role of policy in managing the pandemic.

I think an uncomfortable truth is that many different groups have an incentive to believe that policy has an impact far higher than it actually does. For policymakers, it provides them with the perception of power as well as a clear role. For journalists who cover policymaking, it makes for a much more interesting story to analyse decisions that are perceived as consequential and important. For scientists, this gives their research and modelling clear actionable implications. Finally, for ordinary people, it provides a comforting sense of reassurance that policymakers have got things in hand and everything will be fine. While I am not accusing anyone in these categories of bad faith, each clearly has a distinct incentive to hold this belief and this inevitably leads to confirmation bias and motivated reasoning. To be clear, I am also not suggesting that policy has no impact –many decisions taken throughout the pandemic have certainly had clear consequences for better or for worse. Neither am I arguing that the lack of efficacy serves to absolve policymakers of any blame for poor decision making. What I do believe to be true, though, is that the role of policy has been far smaller than many have made it out to be, and the constant reactionary calls for it to step in at every twist and turn have been misguided.

The recent fall in cases, despite the further easing of restrictions in the UK, has left many journalists and scientists baffled and looking for reasons that it is not genuine. Could it be a fall in tests? Could it be schools breaking up for summer? Could it be the impacts of the 'pingdemic' causing many to self-isolate? These people live in a fantastical parallel world where it is policy, and policy alone, that can explain every possible twist and turn of the pandemic. The truth of the matter, as we will see in my next post, is that there have been countless instances in many countries where cases have fallen despite the absence of any interventions or herd immunity plausibly being reached, and yet some still act surprised when it happens.