Man Bites Dog – Developing a Measure of News Concentration

Plus a comment on COVID travel restrictions

There is an old journalistic aphorism which dictates that a run of the mill event, such as a dog biting a man, is not considered newsworthy. A man biting a dog, on the other hand, is much more likely to receive news coverage purely as a product of its unusual nature. Even if two events likely have similar outcomes, the more unusual of the two is far more likely to be deemed worthy of the news, and as a result news coverage tends to focus on rare events, potentially with distortionary impacts. This has definitely been the case during the pandemic, as there have been multiple stories penned on young people who have become very ill with the virus, cases of individuals testing positive despite being vaccinated or previously infected, and very old people getting through the disease with little to no symptoms. All of these are rare events and yet receive overwhelmingly disproportionate coverage in the press.

There has also seemed to be a high demand for bad news during the pandemic – a recent paper found that 87% of US news articles relating to COVID were negative in tone. While obviously, you would not expect a perfectly even good/bad split, this seems very high to me when you consider the enormous progress made on vaccines. It also squares with a second result in the paper, that the sentiment of news coverage was entirely unresponsive to changing trends in case numbers. While it could be argued that the value of negative articles is higher than that for positive articles, since these could promote increased precautionary measures such as mask-wearing and greater social distancing, I personally don't buy this argument. As far as I can tell, the people who tend to consume a lot of COVID news tend to skew towards highly risk averse, and were likely going to take these steps anyway. All the negative news coverage does is fuel more pessimism in these groups. This distortion in news coverage seems to have real effects on decision making. A recent US survey found that 54% of people who had already been vaccinated were still worried or somewhat worried about catching COVID, while only 29% of people who refuse to be vaccinated exhibited the same level of concern. This would seem to be a direct result of the negative coverage of vaccines, with many media outlets choosing to overemphasise the threat of vaccine-evading variants as well as the <100% protection figures based on clinical trial results for symptomatic infections. There has been distressingly less focus on the absolutely remarkable fact that all of the vaccines were 100% effective against hospitalisation and death, which is ultimately what we truly care about. While, thankfully, vaccine hesitancy has not been a problem in the UK, it has been in the US and I think that news outlets have played a significant role in this.

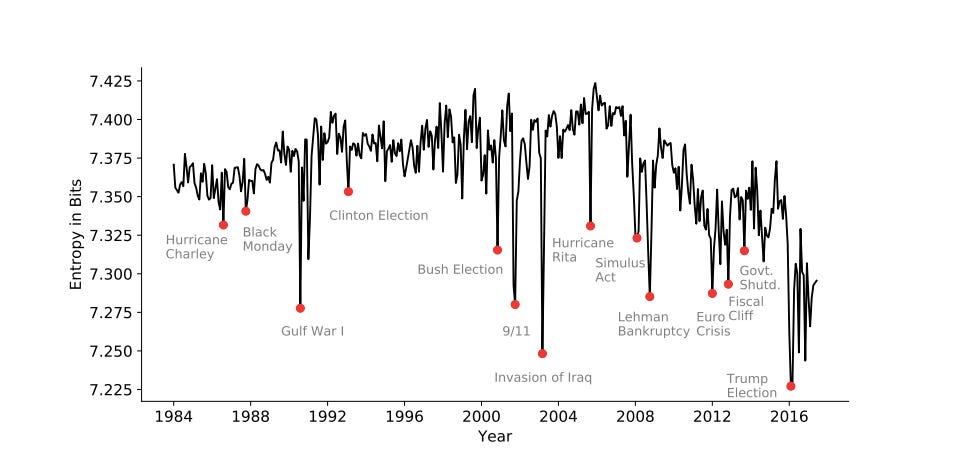

With this belief in mind that news coverage is potentially important for shaping decision making, in a recent paper with Nikolas Kuhlen we set out to measure variation in the content of the news over time. In principle, this could be quite a hard problem as the news is such a high-dimensional object, but we chose to focus on measuring the degree of concentration present, i.e. identifying times when news coverage is highly focused on a small set of topics. Using a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (a fairly standard machine learning method) on the full newspaper texts of 763,887 articles published between January 1984 and June 2017 in the Wall Street Journal, we are able to categorise each article by the topic it focuses on. We can then calculate the degree of news concentration (entropy) each month and look at how this has changed over time.

We find that news entropy is low (concentration is high) during many significant events in recent US history, including wars and natural disasters. Interestingly, however, we find that the Trump election in 2016 represented the highest period of news concentration in our whole sample. This dovetails with an upward trend in news concentration we find beginning in 2008, during the financial crisis, as Wall Street Journal coverage has become much more focused on a narrow set of topics since this time. Unfortunately, we do not have the data for 2020, but we imagine it would show an unprecedented level of news concentration in March and April as the COVID crisis was emerging. A natural follow-up question is to ask whether these news coverage shifts have a significant impact on the real economy, and we find that they do. An increase in news concentration causes a decline in economic production, consumption and employment which persists far longer than the change in news coverage does. We also find that stocks more exposed to the news cycle earn a risk premium. When we decompose the news into economics, politics and culture, we find that news about the economy is far more important for real outcomes than political news, while reassuringly culture news is just noise.

The Problems with Continued Travel Restrictions in 2021 and Beyond

There has been a lot of talk for the last few months about how closing the borders is essential to the UK maintaining control of the pandemic. Yesterday, a cross-party group of MPs recommended that foreign holidays be discouraged to prevent the importation of new variants into the UK. This is “the year of the variant” according to epidemiologist Devi Sridhar. I would actually argue it’s the year or something else that begins with the letter V in all honesty, considering that the UK is on track to offer the vaccine to all of its adult population by mid-summer. While tougher border controls would have probably had high benefits at the start of the pandemic in 2020, I think that this current line of thought around variants is misguided. Bear in mind that the B117 variant that has had the most significant impact on the pandemic originated in the UK. No amount of travel restrictions would have prevented this from happening. Also, once these measures have been put in place it becomes very hard to lift them. The goalposts seem to keep moving for some countries in regards to the criteria which need to be met for them to be relaxed. If the reasoning behind these quasi-border closures is to stop variants coming in, when will this cease being a concern and enable the lifting of them? The position seems to be that borders will need to be closed until covid has been almost eradicated globally, or there is a super vaccine that maintains its potency against all variants. Have no doubts about it, this likely means travel restrictions for the next several years at the minimum. I think it is also reasonable to question the efficacy of this policy for keeping variants out, as many countries placed the UK on the banned list after the Kent variant emerged, and yet this did not stop it from reaching their shores. Finally, there seems to be a line of thought that a new variant could emerge which would send us back to square one. This is just a sensationalist falsehood, and trivialises all the progress we have made. If the worst came to the worst, new vaccines specifically designed for these variants could be developed in expedient fashion, which is exactly what the vaccine producers are already doing.

A perhaps more subtle point is that the policy also disincentivises countries from reporting the discovery of new variants, or even having any kind of robust genomic sequencing program in the first place. To me, there is not an acceptable way to keep all borders closed (or close to it) for an indefinite period of time, on the chance that a problem variant we don't know about now will emerge somewhere. Another common issue with the discourse is that many seem to view foreign travel as serving the sole purpose of holiday trips, but so many in this country have relatives abroad who they have not seen for well over a year now. What message do we give to them? And I haven’t even mentioned the damage this is doing and will do to the already crippled aerospace industry. If we were really serious about preventing foreign variants from emerging, we would be making it a priority to distribute vaccines to developing countries. So far, these nations have received a criminally low proportion of all vaccines, leaving them primed for recurrent waves as we are so tragically seeing with Brazil and India. It is these large waves that sow the seeds for a new variant to emerge, just as we saw with the Kent variant which cropped up when cases in the UK were very high. Unfortunately, border restrictions only strengthen the insular mentality and make a policy like this much more unlikely.