I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope, or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody. - James Carville, Bill Clinton’s presidential advisor

To make what has seemingly become an evergreen statement: it has been a rough month in the UK. After Liz Truss won a painfully drawn-out Conservative leadership contest, she did not waste any time outlining her fiscal agenda. Alongside her (now former) Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, the measures drawn up included a massive energy bills cap (estimated cost £100bn), reducing the top rate of income tax from 45% to 40%, reducing the basic rate of income tax, cancelling planned increases in national insurance contributions and the rate of corporation tax, cutting stamp duty, and a range of other dovish policies. Importantly, these measures were ‘unfunded’ i.e. funded with the issuance of UK government bonds (gilts) rather than tax revenue or spending cuts.

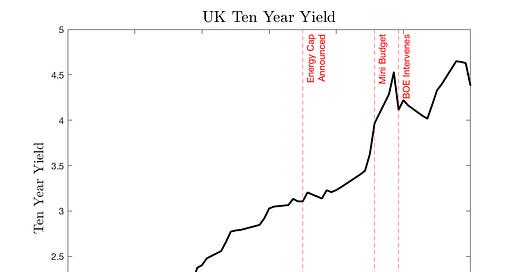

Unfortunately for the two of them, markets were just as quick to punish them. The idea of bond vigilantism is that bond market investors will not tolerate fiscal profligacy unless future surpluses back it. The concept was prominent during the early years of the Clinton administration in the US, which ran consecutive budget deficits before being forced into a fiscal tightening by rising bond yields. It seems a similar dynamic has been at play in the UK. Here is the plot of the yield on a 10-year UK government bond since the start of August:

There is a clear trend upwards initially as the markets gradually priced in the huge fiscal impact of the energy cap. It should be noted that although the cost of this policy was estimated at £100bn, it is highly possible it could well have exceeded that when all was said and done. The government were guaranteeing energy bills for the next two years, essentially taking on an unlimited amount of unhedged commodity risk. I’m almost surprised this didn’t have more of an impact on bond yields, but I suppose markets knew that something drastic had been coming for a while. For what it’s worth, I think this was quite a foolish policy. A cap on unit energy prices means that a large amount of the policy’s cost is spent subsidising the bills of wealthy households since these are the highest users of energy. Support could have been much more effectively targeted towards those at the middle and bottom of the wealth distribution. But this is a story for another day. New Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has shortened the guarantee period to April 2023, which is sensible since it avoids tying the government’s hands in the case of further energy price volatility.

The next clear move in yields comes on 23rd September — the day of the now infamous mini-budget. The 10-year yield increased by 32 bps, an incredibly large move in what is normally a non-volatile asset. The shorter maturity 5-year bond experienced its largest-ever daily yield increase. This clearly represents a response to a fiscal surprise, with markets not anticipating the extent of the dovish policy ultimately announced.

This rise in gilt yields generated its own problems in the UK financial sector, with a swathe of pension funds finding themselves in a serious spot of bother. This in itself is puzzling on the face of it, since a rise in bond yields (all else equal) should reduce the present discounted value of a pension fund’s liabilities, ultimately representing good news for them. However, pension funds had hedged against interest rates falling by using liability-driven investment derivatives (LDIs). The sharp rise in yields had significantly reduced the value of these positions, leading to margin calls where the pension funds are required to post more cash as collateral. The only way they could do this was to sell gilts, leading to fire sale dynamics where the price of gilts continued to fall (implying yields rose) which required the funds to post more collateral, causing further price falls, and so on in a kind of ‘doom loop’. There are serious questions about why these pension funds were doing this, and why the regulators did not see this source of risk as John Cochrane discusses. The Bank of England felt it necessary to step in to buy gilts on 28th September in order to stop this negative feedback mechanism. This intervention kept yields from spiking, at least temporarily.

The reduction in volatility would not last, however. Yields continued to climb as the calendar turned over to October, eventually forcing the Truss government to renege on the top rate of the tax cut, followed by the corporation tax non-increase, and finally causing Kwarteng to be sacked as Chancellor in favour of the more fiscally conservative Jeremy Hunt on 14th October. In slightly humorous fashion, bond yields once again rose after this, although on 17th October when Hunt announced that almost all elements of the mini-budget would be scrapped entirely they did fall.

A few points are worth making in light of this episode I feel:

1) Bond markets have not rejected supply-side economics.

Many commentators on the economic left have triumphantly declared victory against the supply-side reformers after the inauspicious market response to the set of policies. In my mind, this is not what they have done at all. Bond investors do not administer ideological tests — why should they? All they ultimately care about are the discounted cash flows offered by the government bonds. Seeing no future budget surpluses in sight will naturally lower bond demand, pushing up yields. After all, the Clinton administration was hardly pursuing supply-side policies when bond markets treated them the same way in the 1990s.

2) The bond market response does not mean the set of policies are necessarily bad in an unconditional sense.

Once more, the bond market response is a statement on the diminishing fiscal capacity of the UK. It does not necessarily condemn the policies announced, but rather reflects the market’s view that the UK does not have the fundamentals to be able to accommodate them. Indeed, there is a lot of evidence that lowering the top rate of tax can boost growth in the long run by increasing the returns to innovation. Similarly, high corporation taxes are not a recipe for growth by any means, and due to the increase now going ahead the UK will have a higher tax rate than the EU and the global average. It must come down eventually, but bond vigilantes do not believe that the UK can afford to miss out on the foregone tax revenue. I doubt bond markets would have reacted much to these measures in isolation, but combined with the massive fiscal shock that the energy package constitutes, they are simply not feasible. This was more or less the view that Rishi Sunak outlined in the leadership contest — taxes must come down eventually but we cannot afford to do this yet.

3) Yields are rising in virtually all major economies, partly due to the winding down of central bank bond purchases.

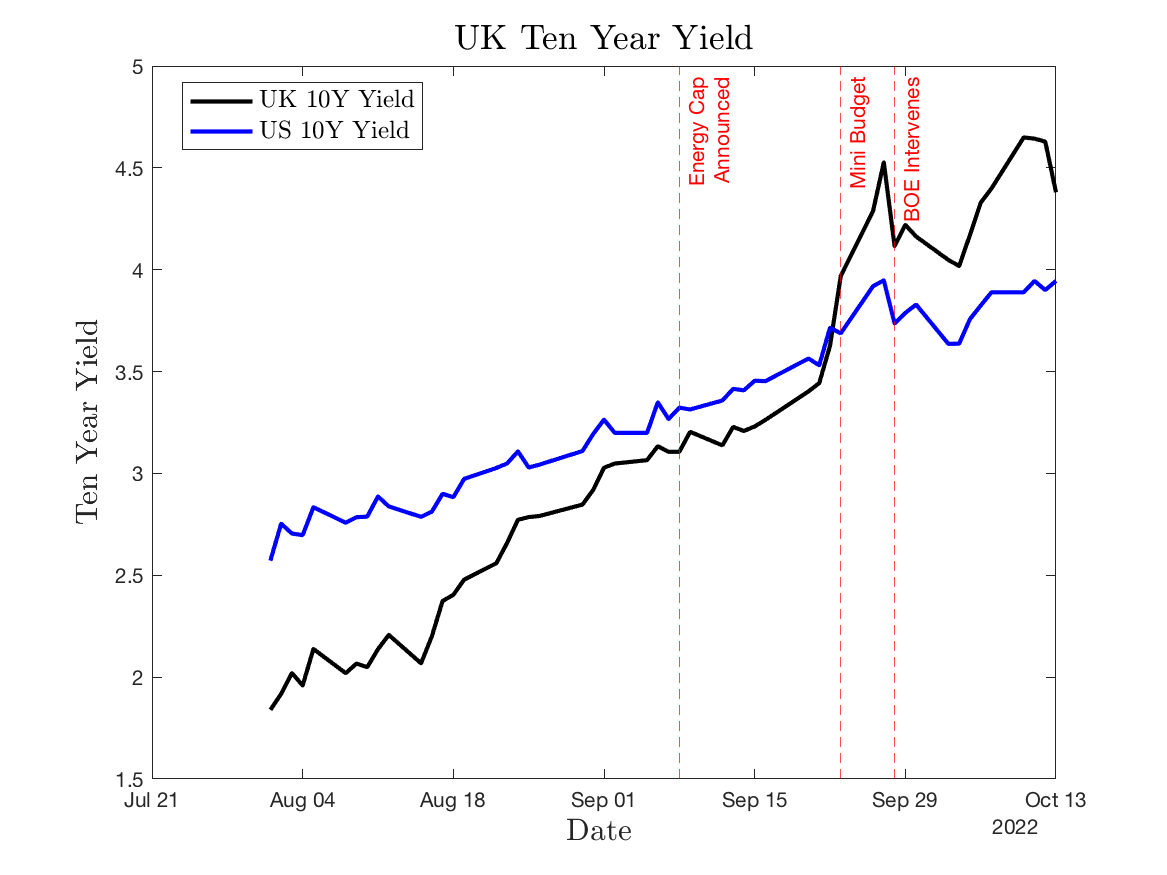

Here is the evolution of the US 10-year yield over the same time period:

It has also risen precipitously, as have most others around the world, reflecting an end to the long bull run for bonds. An important factor in all of this is quantitative tightening — where central banks reduce their balance sheets by no longer replacing assets that reach maturity as they were doing previously. This has meant that central banks like the BOE and the Fed are now far less involved in buying long-maturity bonds than they were, reducing the overall levels of demand. It should be noted that the BoE announced on 22nd September, one day before the mini-budget, extensive plans to reduce the stock of gilts it held. In my view, this large role it had on the buy-side was severely inhibiting price discovery in the bond market, with private investors being crowded out by the central bank which was always willing to pay a higher price for government bonds, keeping their yields artificially depressed. An extreme case of this comes from Japan, where the central bank essentially buys all of the bonds:

As I’ve outlined before, investors being able to bet against and go short in an asset is key for price discovery to take place. But who would short a 30-year UK bond knowing that the BOE might intervene and generate a massive price increase?

The reduced role of the central bank in the gilt market allows the bond vigilantes to play their part once more. The large fiscal stimulus during Covid, which primarily took the form of the furlough scheme in the UK and the stimulus cheques sent to households in the US, notably did not see a large rise in bond yields. However, QE was undoubtedly a major reason behind this, and unwinding it has revealed that many countries have far less fiscal capacity than they may have once thought. The bond vigilantes may continue to get their way as they once did, and the period of care-free budget deficits may well now be in the rearview mirror. Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss would surely attest to that.

Things I Have Enjoyed Recently

This is a great podcast with Adam Tooze interviewed by Ezra Klein that touches on a lot of current economic issues. Monetary tightening has very far-reaching impacts, which we are only beginning to see. Tooze is not someone I always agree with, but he is wonderful to listen to and is incredibly knowledgeable about the global financial system. I’d recommend all his books also.

I’ve only watched the first few episodes, but I’m really enjoying Adam Curtis’s new documentary series Traumazone. The series covers the Soviet Union during the fall of communism from 1985-1999. As usual, Curtis obtains some incredible archive footage. Particularly relevant now for obvious reasons.

Alex G released what is probably my favourite album of the year so far, God Save the Animals. Recommended.

“Heavier vehicles are safer for their own occupants but more hazardous for other vehicles. Simple theory thus suggests that an unregulated vehicle fleet is inefficiently heavy. Using three separate identification strategies we show that, controlling for own-vehicle weight, being hit by a vehicle that is 1000 pounds heavier generates a 40–50% increase in fatality risk. These results imply a total accident-related externality that exceeds the estimated social cost of US carbon emissions and is equivalent to a gas tax of $0.97 per gallon ($136 billion annually).”

We are at a particularly high period of geopolitical risk, with Russia starting to rattle their nuclear sabre once again. A good Substack post by Policy Tensor on this, and a good WSJ article also on the enduring lessons of the Cuban missile crisis.

“Genomics company Illumina just unveiled its fastest, most cost-efficient DNA sequencer yet. The machine will deliver a $200 human genome and will be able to generate 20,000 of them a year.” This is remarkable when you consider that 22 years ago it cost $300 million to sequence the first human genome.