The Brahmin Left and the Merchant Right

A look at the changing relationship between education, income and voting choices

The rise of populism over the last decade across the world has led many to seek the underlying cause of this trend. Roughly speaking, these explanations can be dichotomised into the short-term ones, such as a reaction to the financial crisis or the increase in the prevalence of social media, and the long-term, which typically focus on demographic shifts in preferences and norms or industrial changes like the decline in the manufacturing sector in rich countries such as the US and the UK. A very interesting working paper from Amory Gethin, Clara Martínez-Toledano and Thomas Piketty falls into the latter, as they argue that the 2016 pair of events – Trump's electoral victory and the Brexit referendum result – are in reality a continuation of a trend that began in the 1960s rather than the aberrations which many may have viewed them as.

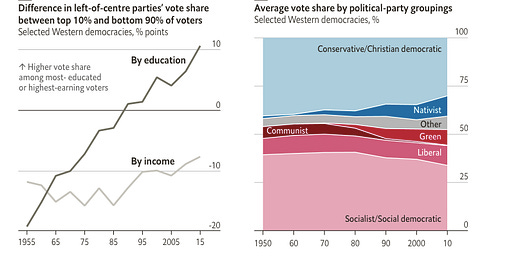

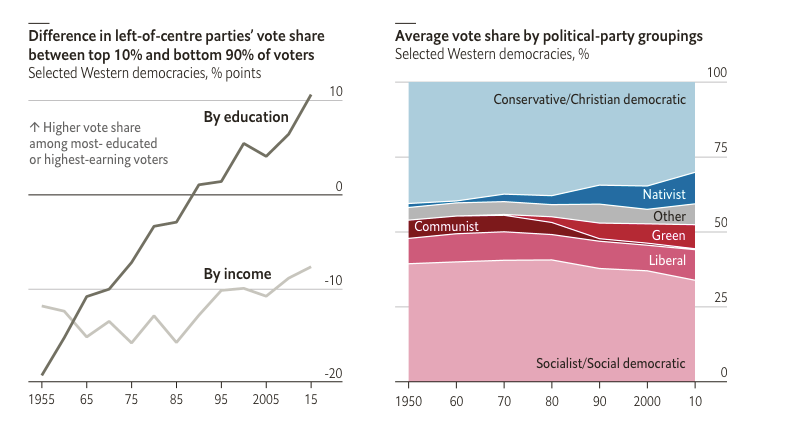

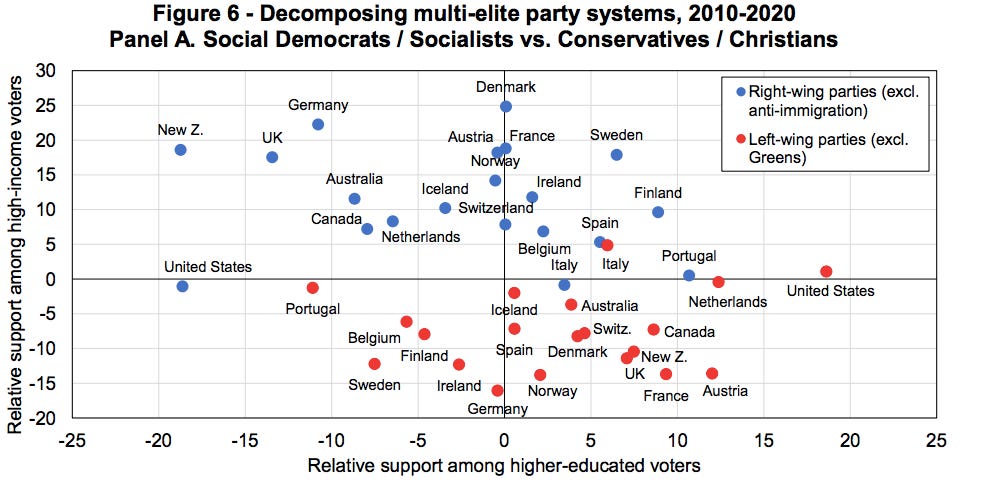

Taking politics at A-level, I recall explicitly being told that in general more educated and wealthier people tend to vote for right-wing parties but, as the paper illustrates, the relationship between voting choices and these variables is significantly more complex. The authors use a rich dataset that covers over 300 elections in 21 Western countries between 1948-2020 and contains data on votes by several socioeconomic characteristics. Since income and wealth inequality has risen substantially over this period, ex-ante one might expect that this has led those at the bottom tail of these distributions to exhibit a higher propensity to vote for left-wing parties who are typically more strongly associated with redistributive policies such as higher taxation on high-earners and the wealthy, and who tend to be more in favour of unions and the minimum wage, which both seem to be effective at reducing inequality. On the contrary, this is actually the very opposite of what has happened in reality, as the authors document a transition from “class-based party systems” to “multi-elite party systems”. Essentially, in the 1950s and 60s, it was overwhelmingly likely across the diaspora of Western democracies that someone who had low relative levels of income and education would vote for a left-wing party (Labour in the UK, the Democrats in the US etc.), and conversely, someone of high income and education would vote for a right-wing party. Since this point in time, this relationship has become gradually weaker and weaker, to the point of divergence between income and education as voting predictors in the 2010s. Whereas the two were almost analogous to each other in this period, there is now a divide between two sets of elites: the high-income elites who tend to vote for right-wing parties and high-education elites who tend to vote for left-wing parties. The authors term these two groups the Brahmin1 left and the merchant right respectively.

Somewhat remarkably, this relationship between education and voting choices is not merely a product of the extreme two-party systems of the UK and US, as the same pattern is also seen even in Scandinavian countries such as Denmark or other European nations like France, both of whom have much more of a multi-party system. Across the spectrum of countries, another commonality has been the emergence of green and anti-immigration parties since the 1980s which has heightened this empirical regularity as it is education levels that are by far the best predictor of a voter's propensity to vote for either of these types of political parties. Parties promoting archetypal liberal policies have seen their vote share increasingly concentrated in the highly educated, while in contrast, the parties who adopt typical conservative policies have seen much broader appeal in the lower educated than in the 1950s and 60s. In 1955, a voter in the top 10% of the education distribution was 20 percentage points less likely to vote for a left-wing party than a voter in the bottom 90%. The trend described actually made it such that by 2015 this had reversed entirely, as the same voter was now 10 percentage points more likely to cast a vote for a party on the left than someone in the bottom 90% of education attainment. Furthermore, the upper 50% of voters in either the education or income distributions have seen no fall in electoral participation rates, whereas those in the bottom 50% have seen a sharp decline, suggesting that the common narrative of political disillusionment among the socially disadvantaged has vast empirical support.

The relationship for income has been much more stable over time, with richer voters still more likely to vote for parties on the right. Other factors such as religion and geography, which have been pointed to as potential key explanatory factors by some, are not found to be of notable importance. The only factor which is shown to be important is gender, with women becoming much more likely to vote for a left-wing party over the last 60 years.

Taken together, the stylised facts documented present a convincing account of a very interesting trend. The simplest explanation I would put forward would be the role of increased education and also that of skill-biased technological change. On the first of these, Western electorates are much more likely to have education at the Degree level or beyond than they were in 1960. For example, even between 2002 and 2017 in the UK, the percentage of the population who had graduated from university had almost doubled in this period from 24% to 40%. Whereas previously it was less important for a left-wing political party to appeal to this group in order to win elections, it is now crucial to do so. On the second point, skill-biased technological change refers to the trend of technology shifts that have favoured the highly educated contingent of the labour force. For example, the rise of computers has been most beneficial for those who are highly skilled and educated and have been able to leverage this technology more readily in their jobs. This has been coupled by a rise in the university wage premium, with increased returns to educational investments, meaning the highly educated are arguably becoming more of an elite and more separated from those who did not graduate university. Perhaps the increasing educational clustering in voting both reflects and exacerbates this socioeconomic divide. Whether these trends continue or reverse will be the crucial factor in shaping Western democracies in the years to come.

This term stems from the Indian caste system, where there was a bifurcation between the Brahmins (priests and intellectuals) and the Kshatryas/Vaishyas (warriors, merchants, tradesmen).

I don't need to read this article to know it's true intent is to promote the Kalergi Plan - a normalization of acceptance in which Caucasoids are rapidly being replaced with Zionist Elite puppets from Pakistan and India, primarily.

Chosen Ones who have chosen similar-minded schadenfreude primitives.